Dr. Ou at ALKtALK

Dr. Ignatius Sai-Hong Ou - Professor in Hematology-Oncology, Medical Oncology

University of California, Irvine

Editor-in-Chief of Lung Cancer: Targets and Therapy

Associate Editor of Journal of Thoracic Oncology

Question: We want to know a little about you. What brought you to study ALK?

I was just a young aimless attending (MD) in 2007. I was looking for a MET inhibitor, and our university had lost an attending physician so I was also doing gastric cancer. I traveled down to La Jolla which is only about an hour from where I work and lived. I was introduced to a Pfizer team: the Crizotinib team. The team had all the phase 1 sites chosen but they didn’t have one on the West Coast. I begged and got Crizotinib into my clinic in 2007 before the original ALK+ lung cancer paper was published in Nature. I consider this journey to be like “Forest Gump.” I was just at the right place at the right time. Looking back, I was going to leave UCI (University of California Irvine) and go to Mayo at Scottsdale because I got the offer in 2008. The protocol for Crizotinib was not even approved at UCI at that time, it took 15 months. But, for whatever reason, I stayed and we opened the trial. I wasn’t paying attention but then I heard over the grapevine that there was a PI (principal investigator) meeting at 4 o’clock in the afternoon (about 7 AM in Korea and Australia). I heard they may have found something in lung cancer and since I was a lung cancer person, they let me listen in on the meeting. The rest is history. We were able to get Alectinib and we were able to get Lorlatinib. So, I was able to start this journey. I have my heartbreaks with patients who passed and we have some miracles with Crizotinib. We could not prevent patients from progressing in the brain. And it was all the way to Lorlatinib that we were very fortunate at this point. We need to keep pushing the envelope. That’s just my story. I wasn’t looking to do a trial and I got the trial. I was going to leave but I end up staying at UCI and the trial opened. Then, we found out it works for ALK+ lung cancer patients. The rest is history.

Dr. Ou had about 20 slides that he wanted to go over.

I am a little biased. Dr. Shaw is now in industry. I feel like I need to carry on the torch to keep the legacy of advocacy alive. I saw the survey at the beginning of the meeting that many patients are just diagnosed within the first one to two years. There is a very important paper that shows ALK+ lung cancer patients have very good survival, close to about 10 years, from Crizotinib and 2nd generation inhibitors. We don’t use Crizotinib anymore so I think the survival is longer. Survival does not mean you crawl to the finish line. Survival means you need to be running all the time and you should be active. You have to extend not only the number but the quality of the number of years too. So, sometimes when I listen to Professor Ross Camidge talk, he says you know “what is the point?” or “what is the goal of treating ALK+ lung cancer?”, the key is not just maintaining as long as you can but also maintaining quality. You kind of just sequence one to another to get to the end point and then you achieve the goal. Regardless, when I first see a patient, I am not looking at 10 years only. I am looking at least 10 years and hope for a breakthrough later. This is not your average stage 4 lung cancer patient. When I first came out of medical school, the survival rate was about under one year. So, it is important.

This is a data from the French Intergroup in 2017. I’m sure the numbers are even better.

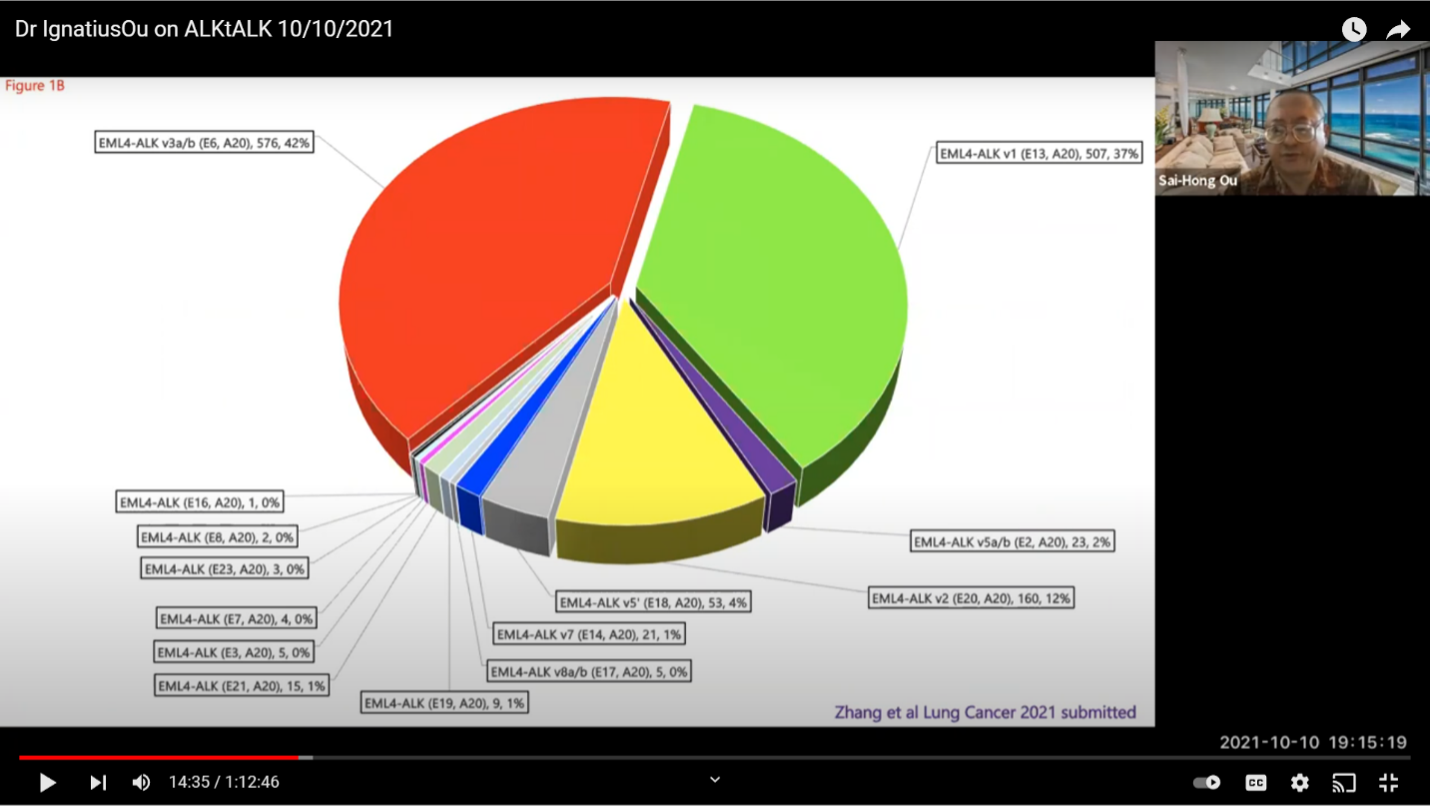

A little about variants. This is a more sophisticated look at ALK+ lung disease. The data shows that our ALK+ lung cancer is not one disease. The EML4-ALK is the primary variant in this type of lung cancer. About 85% of ALK+ lung cancer has the EML4-ALK fusion. You can see the variants are initially named by the order when they were first discovered by Professor Manuel. He discovered variant one and variant two in the same paper in Nature. Then, variant three was discovered the next year. It is shorter in 2D or 3D representation. It is actually more stable and it is bulkier and it is more resistant to ALK+ inhibitors. Then, you have other variants like variant five where it is even shorter but has about the same bulkiness. During the development of all the ALK+ inhibitors, the method of diagnosis was by FISH or immunohistochemistry (IHC). I understand that those were the original methods, but these two methods do not tell you the variant type you have. I think it is important as we get into the 2nd or 3rd decade of this disease, that we cannot just rest on six ALK+ inhibitors. We have to push and push and achieve something more. I know most are doing next generation sequencing (ngs) but we don’t prescribe treatments according to the variants at this time. But, we, as treating physicians, have to have some idea that if you have variant 3 your patient is at a higher risk of relapse and the progression free survival (PFS) is shorter than if your patient has variant one. So, those things are what the treating physicians need to be aware of, and at least plan ahead.

This is a pie chart from two major registries that shows variant one and variant three each consist of about 35-40% of the ELM4-ALK+ lung cancer. There are a lot of other variants. It’s important that we know that not many people are paying much attention to the variants. If they are paying attention, it is to variant 1 and variant 3.

These are the NCCN guidelines. Three of the inhibitors have category one designation. One is better than the other two and I have to say that you cannot just say, well, you can pick any one of three. Then, you can sequence the rest of the medication. I will argue that Lorlatinib is the best amongst the three.

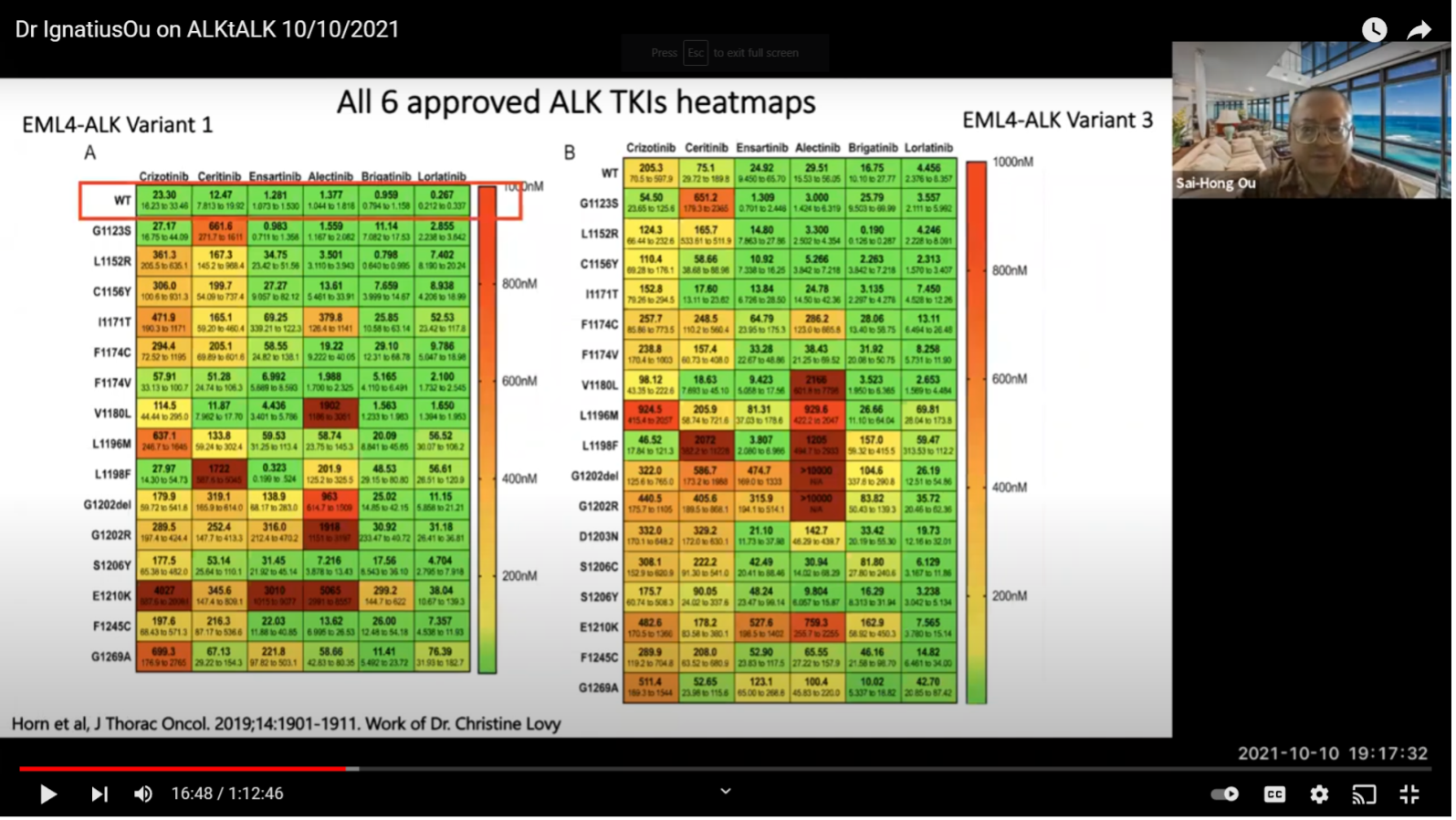

This is the work from Dr. Christine Lovly. I am only looking at the wild type original ALK (boxed in red). As you can see just by using this lot, variant one is much more sensitive when compared to variant three.

If you look at all six inhibitors, you don’t even see the line on Lorlatinib. You see a blip of that on variant three, shown in green. So, this is important for reference and hopefully in the future we will have something that can target variant three specifically. But, it may be a while. At least be aware of its importance.

Questions: What does it mean if you have a variant 3a or 3b or EML4-ALK. What is the difference or what does it even mean?

That is a great question. I think 3a and 3b coexist in the majority of the samples. So, there’s a paper coming out that shows the variant three consists of 3a and 3b in the tumor; 3b is more sensitive than 3a. In the paper, we were commenting that during treatment, you will get more 3a than 3b. So, you get more resistant clones for 3a. Now, we don’t know whether it is just one paper or this can be generalized or not. The difference between 3a and 3b is a different splicing. So, we are proposing to target splicing as part of the treatment in the future. That is a lot of theory. But, 3a and 3b coexist in most cases right now. The commercial technology usually does detect 3a or 3b or both in the tumor. In the liquid biopsy, I think it is harder. At this point, the 3a or 3b does not make any difference. It is only a very scientific look but it does not affect day-to-day clinical decisions at this point. Hopefully, we will determine why and it will be important in the future.

This is just to show that Lorlatinib is the best inhibitor by looking at the IC50. A lot of you may be skipping the National Football League to join this meeting so this is what we call measurable. There are non-measurables and measurables. New York Jets lost today in London. They have a great quarterback Zack Wilson. He has a lot of good measurables. Being a good quarterback, there are some non-measurables. But in Lorlatinib, among all the measurables, it is the best amongst the six inhibitors whether it is variant one or variant 3. Here, you can see the numbers. This is from Christine Lovely’s paper. It is not something we made up. We just abstract her numbers and do a high school project of a bar chart putting the numbers side by side. Those are the numbers. You can see Crizotinib was really good from the beginning but right now rarely anybody really uses Crizotinib up front.

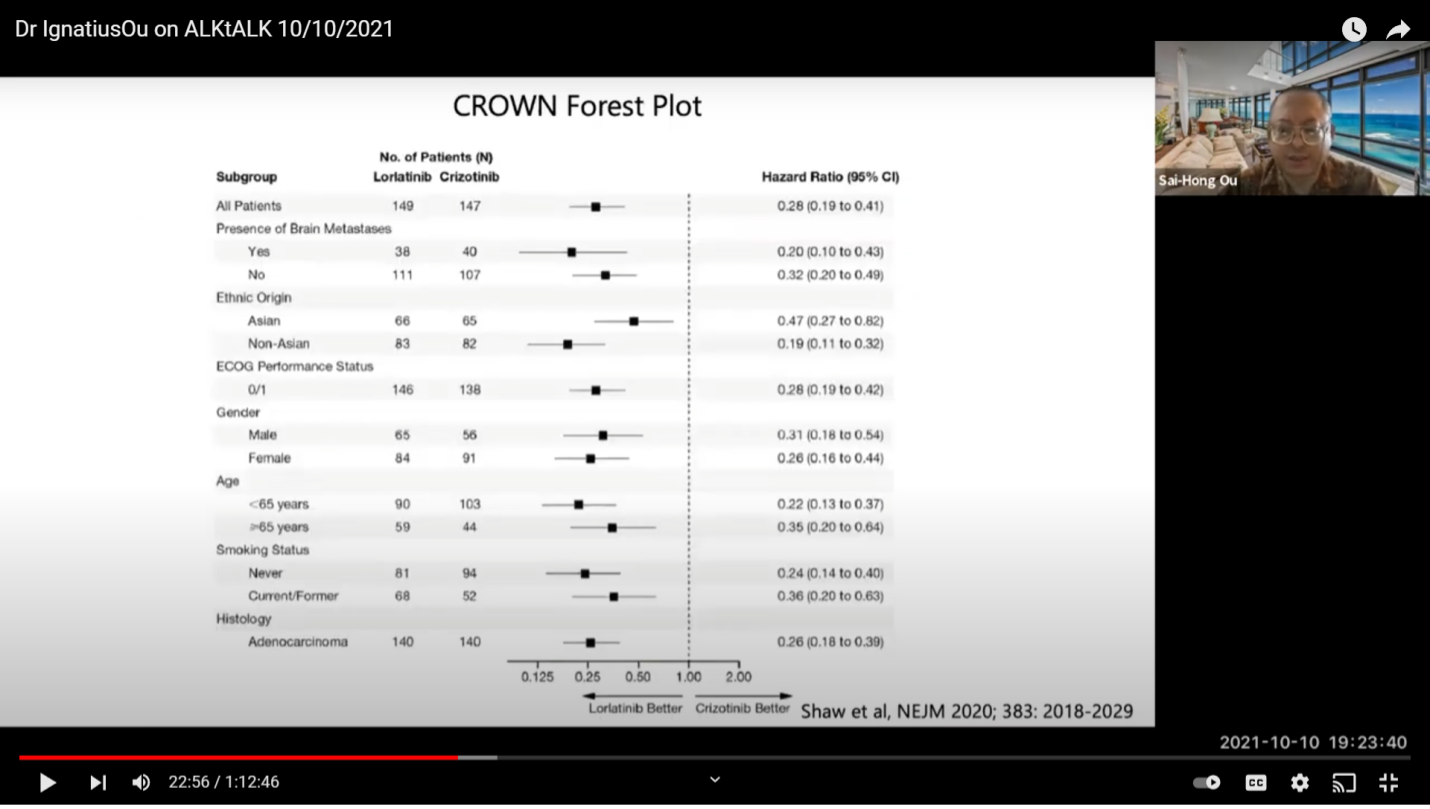

This is the comparison of the studies on hazard ratios (HR). If you just look at the data objectively, whether you have a patient with brain or without brain mass, the green bar is the best so far. If you want to look at progression free survival (PFS), Lorlatinib has not reached that at this point. But, I think it is more than 33 months, the longest of them.

Here is a color matrix. So, this is to look at the subgroup analysis of the four major trials, Alectinib, Brigatinib, Ensartinib, and Lorlatinib. As you can see, whether you are male or female, different ages, brain mets or no brain mets, smoking status, or chemo or no chemo status, Lorlatinib is green all the way. Some of the trials have one or two subgroups that are not positive (red). That means there are rare numbers that may not work there. If you really want to look at comparisons, you want your compounds to be all green for all subgroups. If you look at Ensartinib with this published data, for the patients with brain mets, it’s actually not positive for progression free survival benefits which is a little bit surprising. Ensartinib is not used in the US so it is not as important at this point. This is how I look at it. You just do a color matrix, you show this is what you know, and you can make your own interpretation on how you look at each compound.

So, this is just the subgroup analysis on the New England Journal of Medicine on the CROWN (clinical trial).

This is an important graph from Dr Drilon from Memorial Sloan Kettering and Dr. Lin from Mass General. They were looking at the incidence of brain mets over time for RET+ lung cancer patients, and they used ALK+ and ROS1+ patients in comparison. The black line is the cumulative incidence of brain metastasis over time in ALK+ patients. It is the highest amongst the three common types of receptor-fusions. This is important information for the clinician to know, because when you start treating in 2008 as I did, you realize brain metastasis is a challenge.

Question: As a PI (Principal Investigator) do you think they take brain mets into account when it comes to clinical trials related to ALK+ lung cancer patients?

Not in the clinical trial enrollment but it is considered in the design. I have a couple of designs for you to look at. Whether you like it or not, you can talk to the companies. It’s very important for the clinician to pick the ones that will prevent brain metastasis. Pfizer’s message is that we have the best drug against patients with brain metastasis. It’s very hard to interpret the data because Brigatinib is good, Alectinib is good and Ensartinib is good too.

But for patients without brain met, this is where I want to show this graph from Dr. Solomon. This is on a paper that was just submitted to General Clinical Oncology about two weeks ago. So, the majority of the patients with ALK+ lung cancer do not have brain metastasis at the time of diagnosis; about 60-70%. One of the tasks of a drug is to prevent brain mets from forming. This is what Lorlatinib does. In the paper, the cumulative incidence of brain mets was only 2.8%. It is lower than Alectinib, so Lorlatinib is very good. But for patients without brain metastasis, it is actually 1% on Lorlatinib. This data has not been submitted yet. Hopefully, this will get accepted and we can publicly look at it. Brigatinib is also very good at preventing patients without brain metastasis at 1%. Instead of 60% at 6 years, you are looking at 1% in 12 months. I presented this data to Tony Mok, and he said it’s one year and you cannot assume the trend so they did not follow up. Actually Lorlatinib is following up on that. Dr. Solomon does not have the data but this is being followed up on. The criticism was that you cannot use one year to extrapolate to the other years. The way I look at it, there’s no reason why suddenly the numbers would go up. The trend is going to be the trend because the drug is going to be the same. So, it is 4.6% for Alectinib in the ALEX trial, 1% for Lorlatinib in the CROWN trial. For the sake of argument, it may be six percent at six years versus sixty percent in six years. Now, do the math and of course, you know we can always criticize it as an unknown. But, we need to look at the trend and we need to have a feeling of what the unknown may bring. So, this is important data. Brigatinib can also achieve that so I am not saying just Lorlatinib. That’s the numbers that have been published. I am just correlating the numbers and that’s very important.

Question: From what you are saying, you would typically in practice use Lorlatinib as a first line then?

Yes, I would say yes. I don’t see a lot of first line indications at the moment because it was just approved last year. So, I don’t see a lot of newly diagnosed ALK+ lung cancer patients yet. But, I would. Especially if they started Alectinib early, I may even switch them to Lorlatinib because you are looking at 10 years or you are looking at 20 years. We try to go “for broke.” We try 20 or 30 years. That’s the way I look at it. I don’t want to use the word “cure” but we try to prevent this with drugs like this. Some patients do very well.

This is now the conventional wisdom of how we look at all inhibitors. You have the 2nd generation and the 3rd generation, so I don’t like this classification anymore because it gives you the impression that we should go from the 2nd to the 3rd generation. But, functionally, you all know all these ALK inhibitors, not counting Crizotinib, can only inhibit one mutation. They cannot inhibit compound mutations.

This is a case report of a patient who had G1202R and then was put on Lorlatinib and eventually had a double mutation. Dr. Shaw’s group at Mass General was the earliest to use Lorlatinib and has the most patients with double mutations. We did a literature search to see what double mutations have been published.

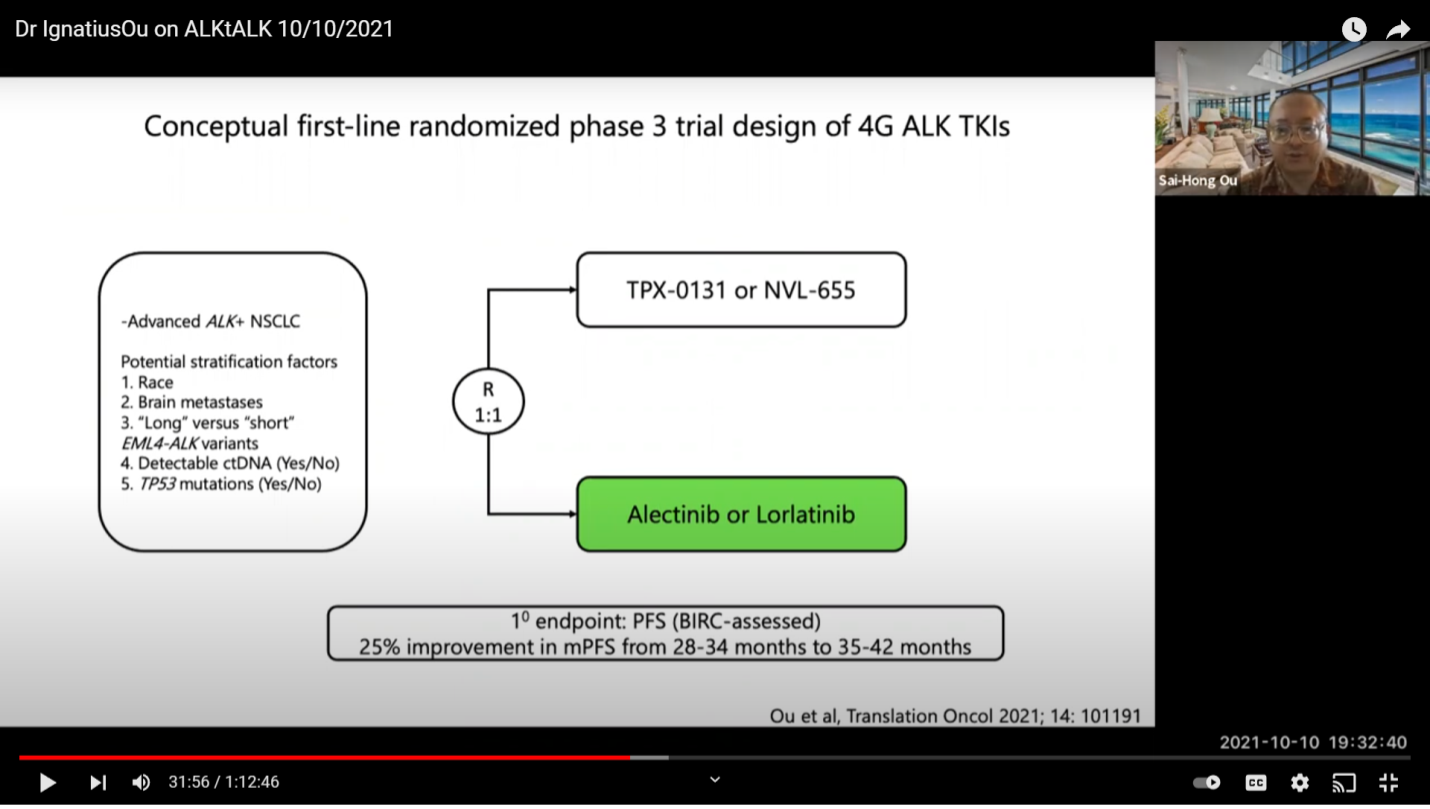

A lot of them have solvent front mutations followed by another resistance mutation. All these mutations will knock out Lorlatinib. So, when you start Lorlatinib in the presence of a mutation already, it is very hard for the drug to perform because the drug is already at a disadvantage. It is different than starting a drug without a mutation first. There are a lot of mutations that show up when you sequence. You try to not develop the first mutation because once you have the first mutation the second mutation will come much faster. It’s just because you cannot expect a TKI to tackle compound mutations at this point. So, right now, there are two companies that are developing what we called a 4th generation, or I would call a double mutant active drug.

The second column are all active drugs against a single mutation. The third column is active against a battery of double mutations on the same allele. So, we have the trial open for TPX-0131. Nuvalent NVL-655 will probably come to the market for clinical trial next year. They will probably have to get their paperwork done early next year to start. So, those are very good options for the patients. Hopefully, they will loosen the entry criteria so people can benefit. Because right now, patients are sequencing drugs, maybe going from Crizotinib to Alectinib to Lorlatinib or Alectinib to Lorlatinib or Alectinib to Brigatinib to Lorlatinib. So, the entry criteria is a little bit tougher for TPX-0131. I understand what they want to do now. Regardless of whether this drug gets accelerated approval or not, they have to run a phase three trial. This is just an FDA requirement and it is also important for Europe and Asia.

This is one trial design where you get up-front treatment. I doubt they will adopt this because it takes a lot of money. When you supply Alectinib, let’s just say the PFS is at 26 months of progression free survival, you need about 250 patients in each arm. Because the incremental increase is going to be at six months, you are looking at about 28 to 34 to 50 months or 35 to 42 months. It’s a very hard for a 4th generation drug to work and to have to supply those drugs. Right now, there is no difference you can see between Alectinib and Lorlatinib. Hopefully, when the CROWN trial data is more mature, it will show that the PFS is longer than 25.8 months. Let’s say 10 months longer. Then, there should not be a choice at that time. We don’t currently know because the numbers are not out yet. You can say “you cannot compare trial to trial” but this is what we do all the time. We shall see. This is going to be a tough trial to enroll because the drug itself will cost about 100 million dollars, if you buy it at retail price and that is what the competitor has to do.

Here is another trial design. This is the approved Alectinib to Lorlatinib. Alectinib has PFS of about 25.6 months. Lorlatinib in the second line setting is about 5-6 months. So, if you look at this arm, 26 plus 7 is about 33 months. If Lorlatinib is used as an up-front treatment, it is going to be for more than 33 months. I think the curve is going to be about 33 to at least 35 months.

Question: Do you typically start them (patients) on Lorlatinib, now that Lorlatinib has been FDA approved?

Yes. If I have the chance, I would say yes.

Question: If the patients already are on Alectinib, would you switch them to Lorlatinib?

Depends. It depends on the timing. It is very controversial. I just switched somebody on that. She was 34 when she was diagnosed and that was around July of this year. They placed her on Alectinib and she had a good response. You know what my feeling is so I switched her. I talked to her and said you know I think Lorlatinib can get you a longer time to progression. Don’t wait too long on Alectinib before switching to Lorlatinib because your cancer will develop resistance. Is it right or wrong? I don’t know. If you have been on Alectinib for a year or two, I will not switch because I don’t think it is more beneficial. If I have a chance to start with somebody very early on, I would do Lorlatinib. It is a clinical judgement. There’s no right or wrong answer. That’s the way I look at it. Within the first few months of diagnosis, it all depends on circumstances. This patient is young at 34 years old. There is no brain mass right now. Let’s try this. I don’t want to wait until all the data is out. If you look at the current data, it is 4.6% for every 12 months for Alectinib and 1% for Lorlatinib. So, if you are young, your chance of brain mets increases every year with Alectinib vs. Lorlatinib. That is my rationale.

This is how they will develop the 4th generation, unless Alectinib plus Lorlatinib efficacy will be shorter than upfront Lorlatinib at less than 36 months. Then, they may have to consider that option. There really is no pushback at this point in terms of design because we don’t know the PFS of Lorlatinib. So, after CROWN reports that it is 10 months better than Alectinib, is it convincing enough to use Lorlatinib as first line instead of Alectinib? We don’t know. But the trial design is artificial. They have “beat” something up. They do not just approve based on science; you have to beat something. This could be one way that this medication will be offered. Whether they are better than Lorlatinib? I don’t actually know because they may be better than Lorlatinib but as a second line treatment. But, if it beats the purpose of developing a 4th generation drug against the double mutants, they still have to do a randomized phase 3 trial.

Question: We have our option of the 4th generation drug like TPX-0131. We have heard some side effects. But, we also have NVL-655. What to do if we have progressed on Lorlatinib? What are options like chemotherapy combined with Lorlatinib?

Yes. Chemotherapy combined with Lorlatinib is definitely used all the time. I think most people do it too, not just me. I have combined all the approved ALK+ inhibitors with chemotherapies before, not just as first line but also Docetaxel (Taxotere) and Ramucirumab (Cyramza) as second line. There comes a time when the tumor even breaks through after chemotherapy. I usually give about four cycles if the disease continues to progress. Because I have patients now that I have been treating for 6 to 10 years and that is what happens when you develop resistance. It is very hard to control. So, there are other options but I was just talking in the hospital about an antibody drug conjugate that is something people may explore in the future. You have to use combinations. So, if you have an off target resistance like a MET amplification, then you are not in the category for 4th generation or the double mutation TKI drug. You have to combine it with an off-label Met inhibitor, that is a very rational combination. I don’t think people can say that is the wrong approach if you have a MET amplification, you have to combine with a MET inhibitor. Now with the approval of amivantamab, it is considered a MET antibody conjugate. We are using a lot of off-label treatment. I think it is not just me; a lot of people treat ALK+ lung cancer patients from the very beginning, you know, 10 or 12 years. Even at 5 or 6 years, you have to use something else.

Question: is there’s ever an opportunity to use immunotherapy with ALK+ patients?

If you look at the IMPOWER 150 trial, they do say that there is some benefit. So, if you look at the numbers they are a little bit better. You know the IMPOWER regime (Atezolizumab, Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel) is approved in the European Union. I tend not to take the ALK+ inhibitor away because it is needed to prevent brain metastasis. So, combining an ALK+ inhibitor with immunotherapy, sometimes you get autoimmune disease or activation of hepatitis, or [inaudible]. So, I tend to not use that with immunotherapy. At this point, I am a little biased because I want to continue the ALK TKI. If I don’t continue TKI, I can use chemo plus immunotherapy. But the problem is once you take the TKI out, suppressing the brain metastasis function is gone. The ability to suppress using chemotherapy is much lower than using an ALK+ TKI. So, you are stuck continuing the ALK inhibitor and adding something to it according to the resistance pattern. Also, maybe you have double mutations and you can go on the double mutant positive TKIs.

This is my last design; a third line design. This is the most scientific or rational design. The drawback is that it limits the market share of the compound. So, I think companies may not like it and they may not adopt this design because they don’t get a lot of patients. This is what we usually do now. You take one of your ALK+ inhibitors. This will be a global study so we can go outside of the US. You can still have Crizotinib and then you can have a “whatever you chose” and then you check for double mutants in the blood. If you find the double mutants, you randomize to what the drug is actually designed for vs. here I use an immunotherapy regime. Because if you are going to run this trial in Europe, this regime is approved in Europe. Or you can use the standard platinum pemetrexed; so, it is chemo vs. an inhibitor. I am not sure patients want to be randomized to this because you have to take patients off the TKI. But this is a clinical trial, and it has to be done this way. So, it’s the non-reality of clinical trial. This is what happens when you have to run a trial because the drugs have not been approved. I think the FDA will have no problem with platinum pemetrexed because it has been proven to work. Europe will probably require the IMPOWER150 as part of the regime and then on progression you can randomize so there’s crossover and patients can still benefit there. It is the most ideal design I would say. Whether this will be adopted by either of the two companies, I doubt it. Because you are limited to drugs in a double mutant situation and you are in a third line situation. But, this is just a mental exercise and you realize how they design the trial will actually affect how the field is being treated. Even though if I use a two to one randomization, more patients get the drug than not. I think in the US, it will be different because I assume both drugs will be approved by accelerated approval while the trial is being done. But, it is a global trial and process and this is how you would have to design the trial to get these drugs approved. My feeling is that the second trial design is probably the best. The problem is that in two years is Alectinib or Lorlatinib the right choice? Because if the CROWN data comes out and it says Lorlatinib is 10 months more than Alectinib, then 10 plus 26 is equal to the median progression free survival of first line on Lorlatinib. Then, you are going to have a dilemma.

Question: We appreciate all the information you have been given us. We can see what you are talking about with the clinical trial design. Patients who have been on targeted therapies for some three or four years or more, when they have the washout period they experience some pretty bad side effects. So, do you ever think that it might be something we can remove from a clinical trial design to not have that washout period?

No. The washout period will probably have to stay, at least for about five to seven days. When I wrote the Repotrectinib protocol for Turing Point Therapeutics, at that time I didn’t do a washout. So, we actually tell you which ALK+ inhibitor in an inducer and which ALK+ inhibitor is inert. We know that Crizotinib and Brigatinib are inhibitors. If you don’t wash out Brigatinib, when you take the testing pill, the level of the pill will go up and you can get more side effects. So, you have to wash off about 7 days. For Alectinib, it is very inert. If you don’t wash it out, it does not affect what you take subsequently. Lorlatinib is the exact opposite. If you take Lorlatinib and do not wash it out, it can actually reduce the level of whatever you take next. So, you get a false sense of security when you go from Lorlatinib to drug X. You don’t actually see the side effects because you think this drug is so tolerable. So, maybe you need a washout for 5-7 days; unfortunately, it is unavoidable. But you do not need to wash out for 14 days. When I was doing the Alectinib trial, they had to wash out for 14 days. We have patients who passed right before they are ready to start because the 14-day washout is just horrible. I cannot keep them alive because the flare is too much. Five days is probably the right amount. We don’t even do it in real life treatment of patients. If we go from Crizotinib to Brigatinib, the FDA does not require a wash out even though Crizotinib will increase Brigatinib levels because Crizotinib is a C34 inhibitor. But, in clinical trials, yes, you have to washout. I would say five days at most.

Comment: That make sense. There are people who can’t handle the washout period to actually even get onto the TPX clinical trial. That is one thing we think is sad that we can’t even test the drug because of a drug flare or something like that. I was just wondering if that is something we can reconsider. But I understand the rationale.

I think you can talk to the company to say 5 days washout and not 7 days or 14 days. When we did the Crizotinib phase 1 trial or the Alectinib phase 1 trial, we had to do dose one and then stop for seven days. Then, we had not only a washout period but a hold period between doses. We lost a few patients because of their one dose day minus seven days. That is another situation that you do not want. You want day minus three instead of day minus seven. There is no reason why you can’t formulate your pK after 3 days. So, I would do day minus three and go ahead. You cannot do a dose minus seven because your one dose is not going to hold the patient for the next week without any treatment.

Question: We know you like Lorlatinib first line and it seems it has a much higher progression free survival (PFS) as a first line treatment. So, I guess the question for most of us is, we are mostly on Alectinib right now. There’s a little bit of fear of switching over to Lorlatinib because if you do Lorlatinib as the first line, what is next?

Dr. Katayama has a paper that shows the one of the resistant mutations that will come out if you use Lorlatinib up-front can be inhibited by Alectinib. So, the difference right now is that we use Lorlatinib as a second-line so you see all the results are double mutations or off-target mutations. But, if you use Lorlatinib as a first line, if you have a target resistant mutation, it will be a single mutation and probably be Alectinib-sensitive. I think you can now go to the TPX-0131 or NVL-655 trial hopefully soon. I also talked to my colleagues about how to design the DVL trials too. I think they need to be patient friendly.

Comment: Please continue to ask for us. We are advocating to increase the number of prior therapies allowed for entry into the TPX trial. As a patient group, we want to allow the highest number of people to be eligible for clinical trial accrual. When clinical trials succeed, we do too: we get new drugs. If you know of anything we can work together on as a group to advocate together, please let us know.

Right now, there is no approved therapy post-Brigatinib; there is no approved therapy post-Lorlatinib first line. The FDA has no approved therapy. From the government, there is nothing post-Brigatinib or there’s nothing post first line Lorlatinib. That is why I think the other companies can develop newer drugs. You say, you can sequence but you know drug development is so different. It is like a vaccine. We all know the FDA has to go through paperwork to approve this or to prove that. Right now, there is no booster shot for Moderna, and boosters are not available for Johnson & Johnson. We all know they are going to work but that’s not proven. That’s government paperwork. So, there’s an opening for all the companies to develop a post-Lorlatinib or post-Brigatinib treatment because right now only post-Alectinib has a treatment, Lorlatinib. Post-Ceritinib also has Lorlatinib. These two first-line approved treatments have approved 2nd treatment lines. You can ask the FDA what happens if I fail Lorlatinib? They will say you know there’s nothing proven. I think you have to convince them to make sure they test the drug in the post-Brigatinib or post-Lorlatinib setting. I think it might be too late for TPX because they have already written the protocol. For NVL-655, they maybe more amendable given that they haven’t written their protocol yet.

Question: In the absence of a brain metastasis, would you give this person Lorlatinib? Would you add Avastin into Carbo and Alimta?

If they progressed on Lorlatinib and no brain mets, it will depend on their performance status. If they are younger or if they can tolerate the treatment. I have done that. I tend not to be aggressive at this point.

Question: How many cycles of carbo would you do before you drop it off?

I do four and drop it off. So, I measure CEA for every patient. I believe it is a very good marker. CEA is one of the cheapest markers and you can follow it on every blood draw. You don’t have to do ctDNA and you don’t have to do scans every three months. I do about 4 cycles and I stop. I do it mostly to reduce tumor burden and then I go back to the single agent TKI.

Question: You have mentioned 10-year survival rates, and such long survival rates I think are eye popping for a lot of our guests we have here. So, is it when Lorlatinib fails that you add chemo with the Lorlatinib? What is progression?

Progression is when you have disease growing. Especially when it is growing in the liver, I don’t want to wait. Lungs too. If there is any radiographic evidence of disease growing, to me it is progression. I also check the CEA levels. If I can see CEA going up and I can see on the CT scan that the tumor is growing, you have progression. If the size of the tumor is big, you really have to do something. If the size is small, like one centimeter, maybe I will wait.

Question: How about radiotherapy? Do you jump on that with radiation?

I am not a huge fan of radiation, especially to the lung, because it really compromises the lungs for the future trials. If you get radiation pneumonitis you are not eligible for anything else. All the 4th generation trials or the double mutant trials eliminate patients who have pneumonitis. So, that is going to be a problem. So, I would hold off any radiation to the chest. There are other modalities you can use to control such as cryoablation. You can even use gimbal embolization in the liver if you have a very aggressive interventional radiology team at your hospital. But I will hold off on radiation. I am on the extreme spectrum of not letting radiation touch the lung.

Question: How do you extend out the therapy if you have a single mutation and not a double mutation? Do you keep on extending that out with chemotherapy that is continuing to work?

Yes, I would give a few cycles of chemotherapy to make sure the tumor shrinks. Then, the CEA drops and then I will stop and then continue. If it starts going again, I will do something different like another chemo. You can potentially try some of the antibody drug conjugates in the future.

Question: what is the antibody drug conjugate that you are referring to?

They are targeted therapies. One of the very provocative studies is from Daiichi Senkyo’s compound Trop2 ADC (antibody drug conjugate). In their phase 1 trial they actually looked at patients with EGFR mutation and ALK mutations. Most of the patients were EGFR patients. They got about a 30-something response rate. It was presented by Eddie [inaudible] from UCLA.

Question: What is your opinion about using an ALK+ inhibitor with a Shp2 inhibitor or Trop2 ADC in a post-Lorlatinib setting without targeted mutations? What options would you consider before second line chemotherapy?

Well, my personal experience with Shp2 as an inhibitor is a little bit disappointing. We have two different combinations and they are not as easily tolerable. I know MGH (Mass General) is doing one and we have a trial open on Shp2 plus Lorlatinib. But I am personally not very high on it. It is just me.

Question: The latest Japanese trial shows that progression free survival is higher for Ensartinib for variant one and variant three for Asian patients against Alectinib. Do you know anything about this? Can you comment on this trial?

I am not aware that Ensartinib has a higher PFS than Alectinib. For variants, variant one always does better than variant 3, no matter which medicine. Ensartinib is trying to find a niche. If you look at the JAMA oncology publication, the subgroup analysis in patients with baseline brain mets was not significantly improved. Ensartinib’s side effect is a pretty bad rash that no other ALK+ inhibitor has. So, I think they are stuck between Alectinib and Brigatinib, but Lorlatinib is already there. Ensartinib is still not yet approved in the US. Ensartinib is not approved as a second-line so no one has really good experience in giving Ensartinib at all in the US. From what I think, Ensartinib should be compared to Lorlatinib and not to Alectinib.

Question: I love that you use the CEA markers. I think Dr. Camidge talked a little about it too. He uses these markers as a less expensive way to look to see if cancer is growing. Are you an advocate for us doing next generation sequencing (NGS) upon progression to figure out what’s driving the cancer each time?

I think next generation sequencing is good. The most critical part is to start at the time of diagnosis to have a next generation liquid biopsy because lots of patients do have liquid biopsy at the time of diagnosis. So, you don’t know whether they have detectable ctDNA or not. CEA is actually a fascinating marker. I use it for almost all lung cancer whether it is one with a driver mutation or not. It works. It works with small cell lung cancer. It works in mutation negative patients. It works in squamous cell lung cancer. It works in EGFR mutant lung cancer. It works in ALK+ lung cancer. It’s a very good method because it gives you a sense: something is going on and you need to be careful. If CEA drops down, that’s good. But, if it keeps going up, I know patients gets anxious. But, I think it is actually much better and faster marker because you don’t scan it. You only scan every 3 months. Most patients are doing very well and they are asymptomatic. You can’t tell what’s happening and you cannot do liquid biopsy every month. Somebody has to pay for the tests. CEA is a very good marker. It is one of the best markers. I would never have believed it when I first started out. I thought this is just nuts. Only the people who don’t want to scan use it. I think they are lazy. They don’t want to scan every six months. Japanese like to use CEA. But, now, I completely switched my view. Everybody gets CEA marker testing. Because when you go to the lab and you are getting lots of information like CBC (complete blood count), protein albumin, chloride, bicarbonate or liver enzymes but they don’t get CEA. Sometimes I get upset because I don’t see CEA being tested, that is the most important marker.

Question: I guess you would get a little opposition from oncologists about testing CEA. I know my doctor for one asks “what if it goes up and I don’t see where it is?”. I cannot treat anything that I cannot see. How do you respond to that?

You don’t change a treatment based on CEA but it gives you something. If you follow CEA enough, it is a telltale sign; it is like a proverbial canary in the coal mine. If you follow it very closely, even if your CEA is 10, you will still know something. We are not changing treatment because of a CEA rise but it gives you a sense of a warning that something else should be done. If the scans are stable but the CEA is going up, then I don’t change treatment but it makes me look deeper. Scans still give the most important information. CEA is like secondary information. I want to have multiple sources of information. CEA is a very useful marker in about 90% of my patients.

Question: This is another controversial one. What do you think about doing lobe surgery on a stage 4 patient? For advanced patients, do you think doing surgery is actually something that can benefit them?

I do. I actually do. If your only site of disease is a nodule in the lung, let’s say the right upper lobe. Then, you have some bone mets. I think it is a possibility or I will wait until the tumor starts to grow. It all depends on the location of the tumor. If it’s in the left lower lobe and you have to take out a big chunk of the lung then you have to be very careful. If it is in the right upper lobe, I think that’s much easier. Also, you have to preserve your lung function. So, I am actually a big fan of that. There’s also wedge resection. So, you have to judge the situation. If the nodule is in the middle of the lung and you have to take out the whole lobe, then that’s different. If the nodule is on the periphery, you can do a wedge resection. I actually prefer a wedge resection to radiation because you can get the tissue and you can do more molecular profiling. For radiation, you just radiate and you don’t gain more information. I know a few surgeons who would do it and I always refer my patients to them. There are surgeons who will not do it; and there are some good surgeons who will do it. I would do it if the circumstances were right and it is much better than radiation in my opinion.

I think you probably have seen the Brigatinib story a few years ago. They show a patient with a nodule that has a G1202R mutation and they treat him with Brigatinib. They keep on showing the nodule. I just said, “Why don’t you just take it out?” It’s a measurable disease, I understand, but in ALK+ lung cancer the chance of finding a solitary metastasis is low. It is lower than EGFR. So, you have to be very careful and you have to think about what you are doing. You don’t want to compromise lung function so you can’t get on to the next trial. I routinely do not have any radiation because radiation will damage your lungs. Despite what they claim about pinpoint radiation, you may have pneumonitis and then you are out of all available trials. For a wedge resection surgery on the edge of your lung, mostly in EGFR mutated lung cancer, they are not as aggressive with the metastases. Some of the metastasis can be just in the lung. For ALK+ lung cancer, it is less likely. More of the ALK+ lung cancer patients can have metastasis in the liver where it is not as easy. Treatments tend to be more aggressive, and you want to go for the liver with chemo and with an interventional radiology team.

You can watch the entire video recording here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4dSjcWa2xKg

Questions have been compiled and organized and may not be in the exact order in which they appear in the video.

Compiled and transcribed by: Alice Chou

Edited by: Jeff Sturm